Placebo

False Affordances & Curious Behaviors

It’s 3 in the morning and you can’t fall sleep. You’re tired of tossing and turning in bed, and you decide to take a pill to be able to get to sleep. You look in your medicine cabinet and find two different types of capsules. One is small and red, the other is larger and blue. After reading the two patient information leaflets, you confirm that both have the same active ingredients and at the same concentrations. Which one would you take to sleep?

If you take the smaller red pill, you’ll sleep fewer hours and you won’t sleep as deeply. On the other hand, the blue pill will give you more hours of sleep and a better rest. The expectations we have for the medicines we take influence their effectiveness. The simple act of having taken a pill improves headaches, localized pain and sleep disturbances. This is the well-known placebo effect.

On the one hand, a larger size predisposes us to expect a better outcome; a bigger pill equals a more effective pill. On the other hand, the color red is instinctively associated with danger. This is probably so because it is the same color as blood. The color blue, however, makes us feel more relaxed than other colors. This might explain the blue pill’s greater effectiveness. The same experiment works all over the world… All over? No! A country populated by unyielding Italians still always defies this experiment.

We could relate Italian passion for their national soccer team to the color blue (azurre in Italian) in such a way that when an Italian man sees the color blue, his subconscious automatically relates it to soccer. His cultural conditioning erases the placebo effect of tranquilizing blue… perhaps. Today I want to talk about the placebo effect in our objects and products.

False Affordance

According to Wikipedia, affordance is:

An affordance is a quality of an object, or an environment, which allows an individual to perform an action. For example, a knob affords twisting, and perhaps pushing, while a cord affords pulling.

Wikipedia

Similarly, a “False Affordance” is an apparent affordance that has no real function; that is, the user perceives an object to have a possible action, which in reality does NOT exist. Put that way, it doesn’t seem very interesting, but with an example it will be understood better.

We live in an environment surrounded by buttons and switches. You press a switch and the doorbell rings; you press another one and a bottle of fresh water falls from the soda machine. This behavior is constant. Using buttons, we give orders, and our orders are listened to and interpreted. Neither how it works nor the orders that are transmitted interests us. We are only interested in the result of our request.

A “false affordance” would be buttons placed in such a way that they give the impression that they perform a function, but they really do NOT. These buttons are known as “Placebo Buttons,” and we’re surrounded by them.

According to an article published in 2008 in The New Yorker, most door close buttons in elevators don’t work. In some cases, these buttons broke years ago; in others, these buttons existed but only worked with a key used by maintenance workers or emergency personnel; other times, the functionality of closing with the button was not included in the installed elevator; and in most cases, there wasn’t even wiring to connect the button. Conclusion: in a large percentage of elevators, this button did not perform any function.

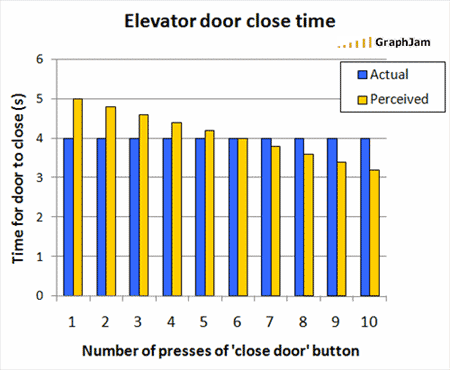

But how does this fake button work in our brains? After the button is pressed, a few seconds later, the door will close. It has to anyway. Your brain will activate the rewards system, and its interpretation will be that the system works correctly at your request. Your behavior will be reinforced. In the future, most certainly, you will continue to press buttons to close doors. What’s more, the more times you press the button, the shorter the perceived elevator door close time will seem to you:

Source: Placebo buttons, false affordances and habit-forming

Within our systems, the buttons, controls, options, etc. with “false affordance” can offer a positive illusion of control. Strategic use of these elements, depending on the context, would improve the perceived quality of our products.

Buttons for pedestrians at traffic lightsare another fantastic example of the placebo effect and the sense of control in everyday objects. For some time now, computers have been in charge of the traffic lights in our cities. But there was a time when crosswalk buttons allowed pedestrians to change the status of the traffic lights from red to green. The vast majority of these buttons don’t work nowadays, but replacing them or removing them would be so expensive that city councils keep them there even though they are inoperative.

The feeling or illusion of control is completely natural for us. That’s why we like to think that we have the ability to influence outcomes , even though deep down we know it is random. For example, it has been proven that when playing craps, we tend to throw them harder when we want to get a high number and softer when we want to get a low number. It doesn’t matter that we are aware of the impossibility of our wishes. The placebo effect and the sense of control remain.

That is why I want to end this entry with something amazing that will improve your life in the silliest way. I present to you the “Placebo Button”. Visit this website, type in what you want the button to cure and click on it. We all know that this button won’t do anything, but you can’t tell me that a pleasant feeling doesn’t wash over you when you click on it. It’s crazy. It’s science. It just might work.

Happy Mardy Gras!

Follow @NoamMorrissey Tweet