Scale

Design Grows Up

In 1775 James Watt created his rotary steam engine. This landmark invention kicked off what we now call the first industrial revolution. It was the first in an avalanche of new discoveries. The application of these technological developments (new products) would have a dramatic impact on the lives of millions of people, principally in the West at the outset.

New methods of manufacture were created that allowed production to increase, reducing the price per unit produced, giving rise to economies of scale. For the first time in history, great sectors of the population had access to products (advanced technological developments) at a reasonable price. Nominally, we refer to this new segment of society that could purchase these new products as consumers. At first, they were satisfied with access to new products that improved their day-to-day tasks. After this initial satisfaction, consumers became more demanding and were more and more concerned with the relationship between form and function.

The field of design appeared, with two motivations behind it:

- For the first time there was a separation between an object’s form and its construction. Craftspeople who apply these two concepts to one sole piece no longer existed.

- As a large number of inventions/products appeared, there was a new professional role for someone to think of what they should look like. This new specialist in form was in high demand.

Initially, the design process was left to amateurs and the form given to new inventions/products was guilty of nostalgia for styles of a bygone age; imitating stylistic elements of the Renaissance, the Baroque or the Gothic, for example. Form was adornment, giving rise to strange objects, like this one, for example.

This is a Renaissance-style sofa, strange because the sofa as a piece of furniture did not appear until the 19th Century, while the Renaissance flourished between the 15th and 16th Centuries.

Suddenly homes, streets and the world became flooded with new products, new inventions. The “Arts & Crafts” movement would later describe the products designed during this period as “marvelously horrendous”. New design professionals were waiting in the wings. William Morris and John Ruskin in Britain would accuse capitalism and industrialization of being responsible for the ugliness of the time.

Arts & Crafts did not seek beauty in the past; it found it in nature…Outside the cities, far from the factories… Nature: its animals, its plants, its forms. Through their designs they sought to improve peoples’ lives.

From theoretical and political positions, designers started to question the usefulness of form and design showed its more strategic side. Throughout its evolution and maturation, design still had to resolve the challenge of scale. One of the first products to bring together demand, technology, scale and design was a chair: the Thonet Nº14.

Bending wood

A small technological evolution, being able to bend wood in any direction and angle was a landmark moment in design. The oldest known technique for bending wood has its origins in the construction of boats. Wooden planks were exposed to steam; they were then fixed to curved molds while remaining at high temperatures. With this system, the wood could only curve in one direction.

From 1830 onwards, Michael Thonet, a German carpenter experimented with a new technique to curve wood. Beech wood battens or slats were exposed to water vapor at the specific temperature of 150º centigrade. There were then fitted to iron frames, which gave them their curved form and the slats were allowed to dry. This method allowed them to achieve a high level of stability and the wood could be bent in any possible direction. This new style of production allowed them to work the wood and give it a completely new appearance (form).

Michael Thonet used this new ability to create chairs that looked completely different, his greatest creation being, without a doubt, the Thonet nº 14. The design of the Nº 14 irradiates light and elegance; the use of wood underlines its natural appearance and enhances the design. The new style of the Nº 14 was completely aligned with the aspirations of a new class of consumers; society was on its way to a bright and elegant future.

Nº 14 was conceived as an affordable chair that was within the price range of new consumers. Thonet created it as a chair for the working classes, and its price didn’t change for more than fifty years.

The Nº 14 was the first mass-purchased item in the history of design. It is the only design created in the 19th century that continues to be produced today. By the start of the Second World War over 50 million chairs had been sold. The secret to its success lay in its production and distribution.

“Here’s the simple truth: you can’t innovate on products without first innovating the way you build them.”

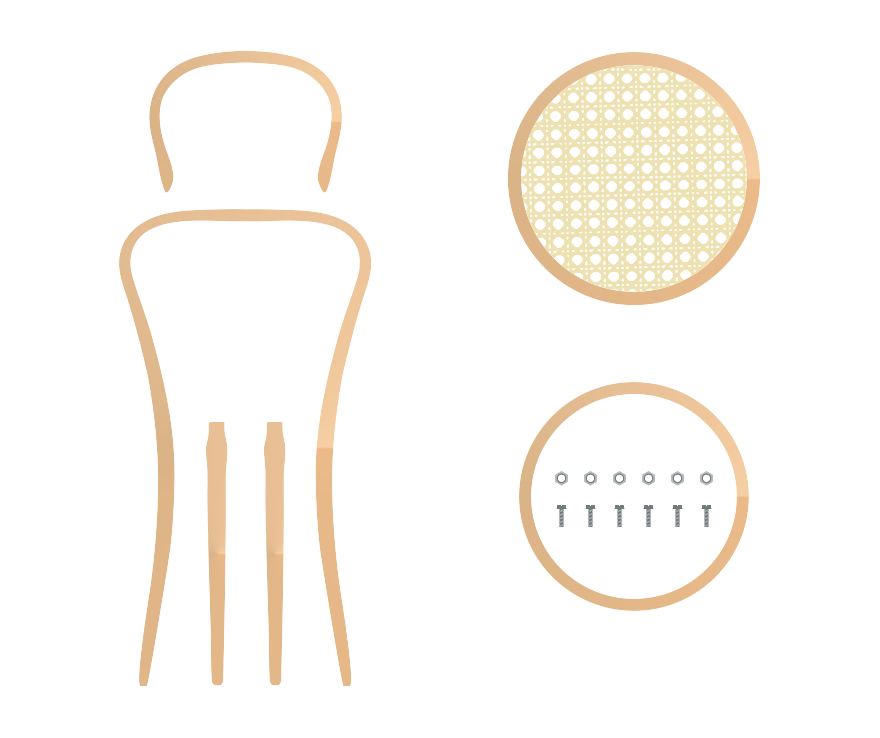

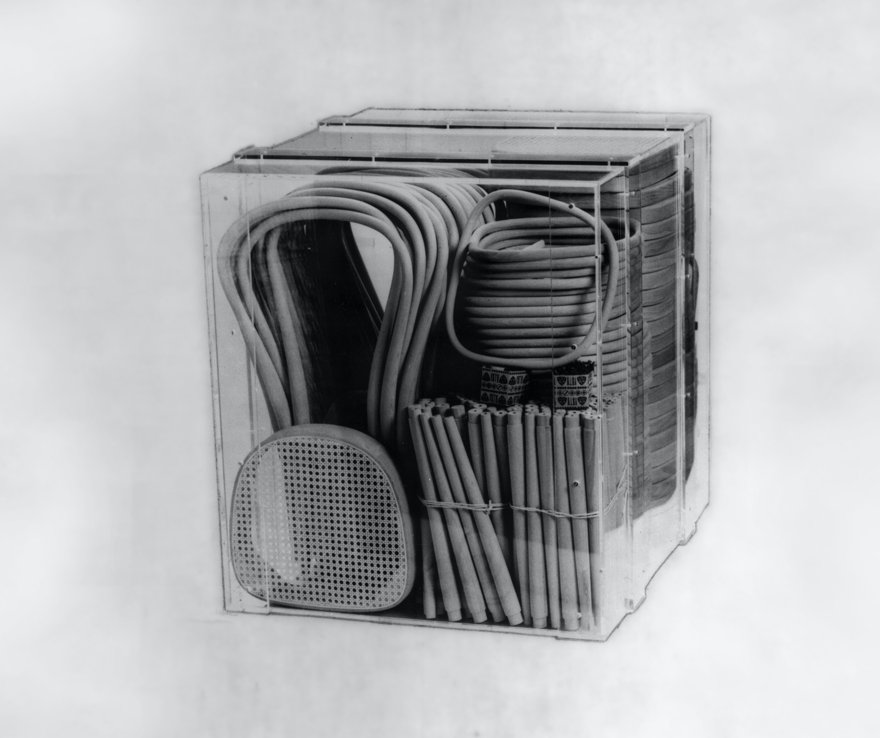

The Nº 14 was made of five parts, six nuts and their corresponding bolts. This meant that if one chair got broken it could be mended with parts from other chairs. As it was made from simple parts it could be transported much more easily and compactly. The package did not take up much space, so it was also cheaper to transport to other countries and could be easily put together once it had arrived at its destination.

Le Corbusier was a fan of the Nº 14:

“Never before has anything been created that was more elegant or better in its conception, more exact in its execution, or fit for its use.”

The success of the Nº14 represents design’s coming of age. A process that started with the industrial revolution, where for the first time technology, demand, large-scale manufacture and design came together to create an object that was at once sublime, elegant and useful.

In My Opinion

In my opinion, there are various factors that come together at historic moments to bring about the appearance of objects as extraordinary as the Nº14. Advances that appear simple – such as bending wood – become opportunities to build things in a different way. Construction. These are metaphors that open pathways to creating products that are simpler, more useful and better built. Moments of maturity in which we free ourselves from technological complexity, to be able to continue to scale up.

That’s to say, to the extent that demand puts pressure onto complex environments, the arrival of certain innovations, which appear to be simple, project metaphors that allow you to solve and harmonize the problem of demand. This allows design to explore new possibilities in the relationship between form and function. The development of interfaces based on components could be the modern day equivalent of the Thonet Nº14.

Components

A component is a reusable piece of interface.

Component-based design

Component-based design is aimed at generating standard solutions to recurring problems that users encounter, through combinations of various pieces of reusable interface (components.)

These two definitions are the basis of large-scale design, and its real and metaphorical impact is redrawing the way that solutions are constructed within large organizations. The points where this could be made more visible include:

- Design. The methodological way in which we attempt to resolve issues that revolve around the relationship between user, context and device.

- Design development. The technical implementation that we use to transform our hypotheses tested with real users into digital products.

- Design organization. The rituals, the structuring and the process by which a design team (more or less integrated with the development team) organizes itself to create a digital product.

When a complex organization is interested in the scale at which it is capable to produce and implement a design, it is more than likely that it has to ask itself questions around these three elements. Dividing products, methodologies, problems, etc. into small, standard pieces that can be reutilised to deal with recurring design issues. This also forces us to be very critical in other aspects:

- Understanding the problems that we are going to standardize and componentize.

- The pieces that we should construct and the resources that we have at our disposal to do so.

- The optimum way to build them and to distribute them to the people that need to use them.

- How to document our “quick-fire” solutions so that they are understandable both in terms of their rationale and their use.

Companies are changing both on the inside and outwardly in their relationship with their clients. Components (quick solutions to recurring problems) are a metaphor, a mental framework that helps us to deal with these changes:

- Highly demanding technological and business environments

- The multiplication of platforms, screens and devices

- Service and customer contact points as yet another activity for design teams.

- Larger and more complex global companies in terms of their structure and organization

- Geographically separated strategy and development teams

Scale matures

As I want to illustrate with the story at the beging of this post, Design continues to evolve in terms of maturity, although this level of maturity is different in every company. There are different models for describing an organization’s level of maturity, but if we unify these models we could stay that there are four levels:

- Design does not exist within the organization

- Design is simply a way of implementing technical solutions

- Design is part of the product and is integrated in the product

- Finally, design is a strategic force and influences business decisions that shape the product

In my opinion, the latter level of strategic design is not the highest stratum that design can reach. The next step for a company to reach in terms of design maturity is its dematerialization.

I will try to explain this statement. Companies that manage to organize their strategy around design make information and knowledge become part of the culture. This culture offers, as a sub product, consistent products and service, efficient and high quality processes. All these products and services have a high level of reusability, thanks to the materialization of a common language, which is shared throughout the whole organization.

The construction of a common language consists of selecting from within the whole universe of possibilities, a concrete way of problem solving, a concrete way of expanding our knowledge of the problem, a concrete way of developing possible solutions to this problem, a concrete way of validating our solution and a concrete way of developing our solution. By making everything more concrete, it means we can act more quickly and our processes are far less inefficient.

Constructing a common language therefore consists of specifying, selecting, reducing the universe of possibilities to those that are really efficient, and documenting rapid solutions to recurring problems. Information and knowledge as intangible goods advance in the process of dematerialization, to a lesser level of entropy, as an emerging order arises.

The culture of pure knowledge offers companies the possibility of moving from a material environment to one of intangible goods. These intangible goods drive companies to reorganize employees, resources and their own objectives as a company in order to:

- Get ahead of the rest of the market. Adapt to innovation

- Finance themselves in a way that suits their needs. Economic sustainability

Components (pieces of interface that can be reused for known issues) are an innovation, and above all, a metaphor; something that appears to be simple, but is advancing inexorably in the solution and harmonization of the problem of demand. Design uses both this innovation, and above all, its metaphor, to move forward towards the economy of the intangible, knowledge. It is not that material goods lack value, but rather that proceduralization and standardization are more valuable from a cultural and economic standpoint.

Over three years ago, in our small studio Realized, we asked ourselves how we should face these challenges. We started to construct our first design system. For more than a year, we have continued to advance in this reflection on scaling up from within a larger and more complex organization Sngular

Design remains important, but more and more we are letting go of tools, processes, methodologies to be become lighter, more efficient, more reusable. Our knowledge increases and our role in generating services becomes ever more valuable.

And what was the name of the first design system? Thonet, of course.

Resources & Inspiraton

- What Technology Wants by Kevin Kelly

- Modular Web Design: Creating Reusable Components for User Experience Design and Documentation by Nathan Curtis

- Design as an Agent for Change: The Business Case for Design Systems by Anja Klüver

- Design Management Patterns & DesignOps by Yury Vetrov

Listening to this while writing

Follow @NoamMorrissey Tweet