Revolution

Give me time and I'll give you a revolution

It all began with a talk by Javier Cañada at La Nave Nodriza, in which Javier spoke about his vision regarding designers and design. You can read some of his reflections in the entry: “The day the designer took off his tie” (Spanish). After a time dedicated to meditating, here are my conclusions regarding the relationship between designers, their historical time, and their designs.

The dictatorship of the proletariat context

Pictured above is a porcelain dish that celebrates the victory of the Russian revolution and its new ruling class: the proletariat. This porcelain dish was painted in 1921, in other words, seven decades of Communism were still to come. At the time this porcelain dish was painted, the Bolsheviks had just established a new political reality based on the theories of Karl Marx, with which they sought to build a new world, a new future.

In 1921, the construction of this new reality was an urgent task. Russia had been disastrously defeated in World War I and the Bolsheviks faced two huge dangers: the threat of a foreign invasion and the outbreak of a civil war. The new rulers needed to disseminate the Soviet spirit through any means within their reach, one of them being this porcelain dish created by Mikhail Adamovich.

In the center of the porcelain dish, in the distance, there is a red factory, a symbol of an economic power that belongs to the workers. The factory is at full production, a large white plume of smoke surrounds it, proof of its great productivity. On the left, in the foreground, a man painted with the same red color, and without any kind of detail that would distinguish him as a concrete individual, looks towards the horizon. He does not represent a specific person, he represents the entire proletariat class that is looking towards a bright future.

This porcelain dish in and of itself would not be of interest if it were not for the ideological weight it carries and the time at which it was manufactured, 1921. In Russia, there was an urgent need to launch messages of unity and hope. The entire country was facing the abyss of the civil war, poverty, droughts, and famine, which ended up causing four million deaths. If at some point you go to the British Museum, you can see this incredible porcelain dish first-hand and listen it´s story.

Museums preserve the objects that help us to understand a historical time, a society, the prevailing ideas of a generation, at a concrete moment in time. The objects that now form part of our daily lives will one day hold their own corresponding place in the British Museum (or at least I hope so) and will serve to explain the time in which we lived. The designers of those objects, like Mikhail, will not be disconnected from their historical context.

The birth of nation profession

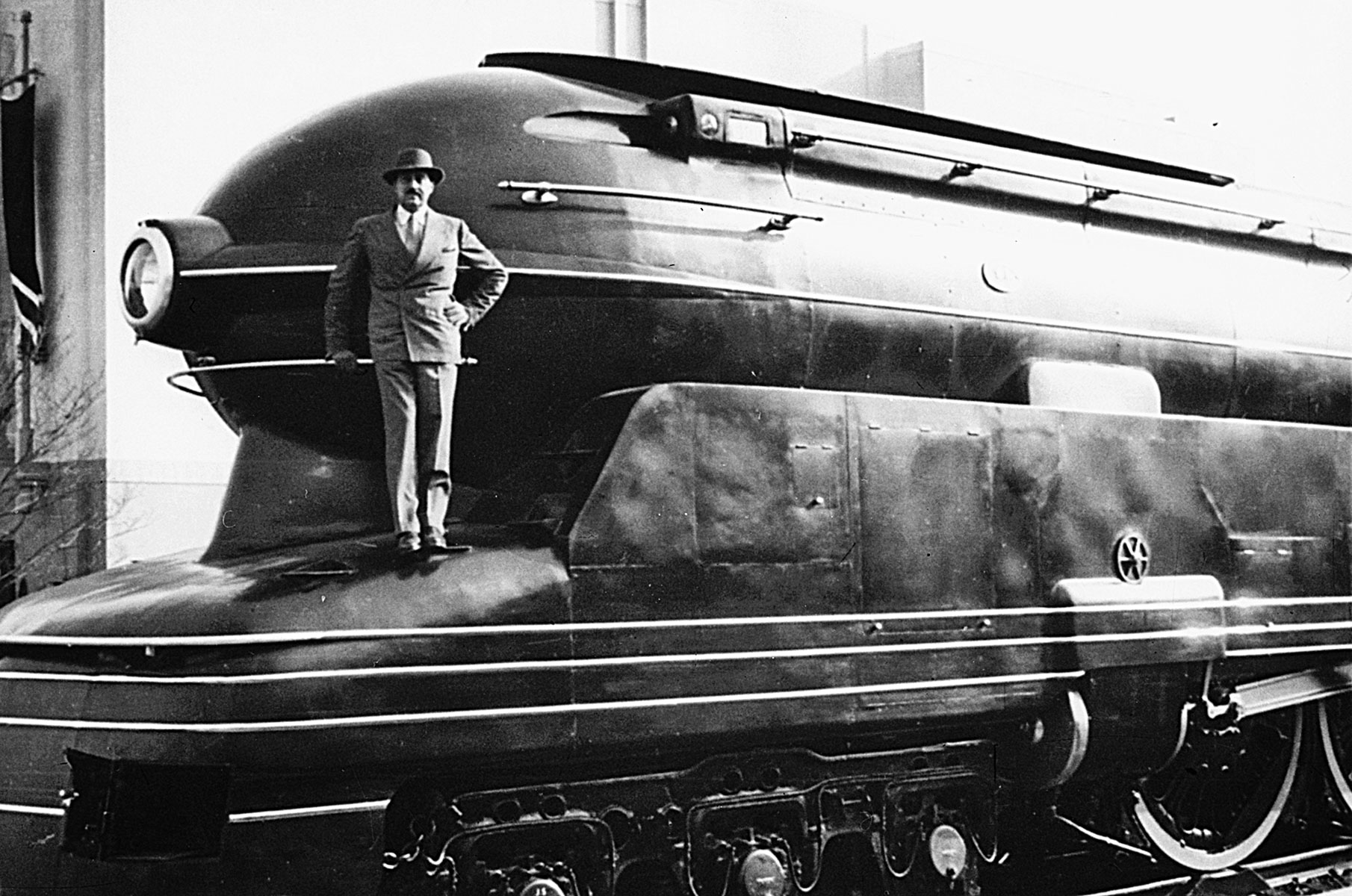

The profession of the industrial designer was born as a result of the deep economic and social wounds that came with the “Crash of ‘29“. The long depression almost completely erased the demand for goods and products and a very high percentage of companies disappeared. The few that survived had to find new ways to sell their products, stand out, and distinguish themselves from others, which saved them. The appearance of the first industrial designers in this era was not a coincidence. Design became a tool to save companies, therefore it should not surprise us that these new professionals quickly enjoyed recognition and prestige.

Design was not the only tool at hand that companies used in order to survive; new materials were applied to new designs: types of vinyl, aluminum, plywood, chrome plating, etc. The depression encouraged the introduction of new and cheaper materials.

Objectified Ideologized

Design, or rather, the solutions designed in this era, like in the history of the porcelain dish, is not disconnected from the context in which they were created. There is always an interpretation, an intention, a direction, in other words, an ideology or a way to explain the world.

El “Streamline” was the solution that the first industrial designers offered to society. A reaction to the dominant Art Deco movement, it was the elimination of ornaments in favor of aerodynamic shapes, clean lines, movement, and speed.

This new way of understanding the shape of everyday objects affected every type of object that you can imagine: watches, radios, telephones, cars, and any type of small household appliance that you could have found in a kitchen from that era.

“Streamline” was a reaction against the established order, a direct response to the economic austerity of the era, a revolutionary, happy vision for the future. A perfect new society dreamed up in an era of depression. Its most defining moment took place in 1939 at “Futurama (New York World´s Fair)”, an event designed by the father of “Streamline” Norman Bel Geddes. Its purpose was to imagine the future world (20 years ahead). Its motto left no room for doubt: “Building The World Of Tomorrow”. As with the case of the Bolshevik porcelain dish, this was design at the service of ideology, the hope of a new order, in a new future.

The American consumers did not just buy a new car or a new toaster; like in Russia, they did not have another porcelain dish; the new designs were the hope, the promise of a better social future. The first industrial designers discovered that a certain type of beauty made the designed objects sell more. Behind the new design there was a new society, a new order.

Design and social order

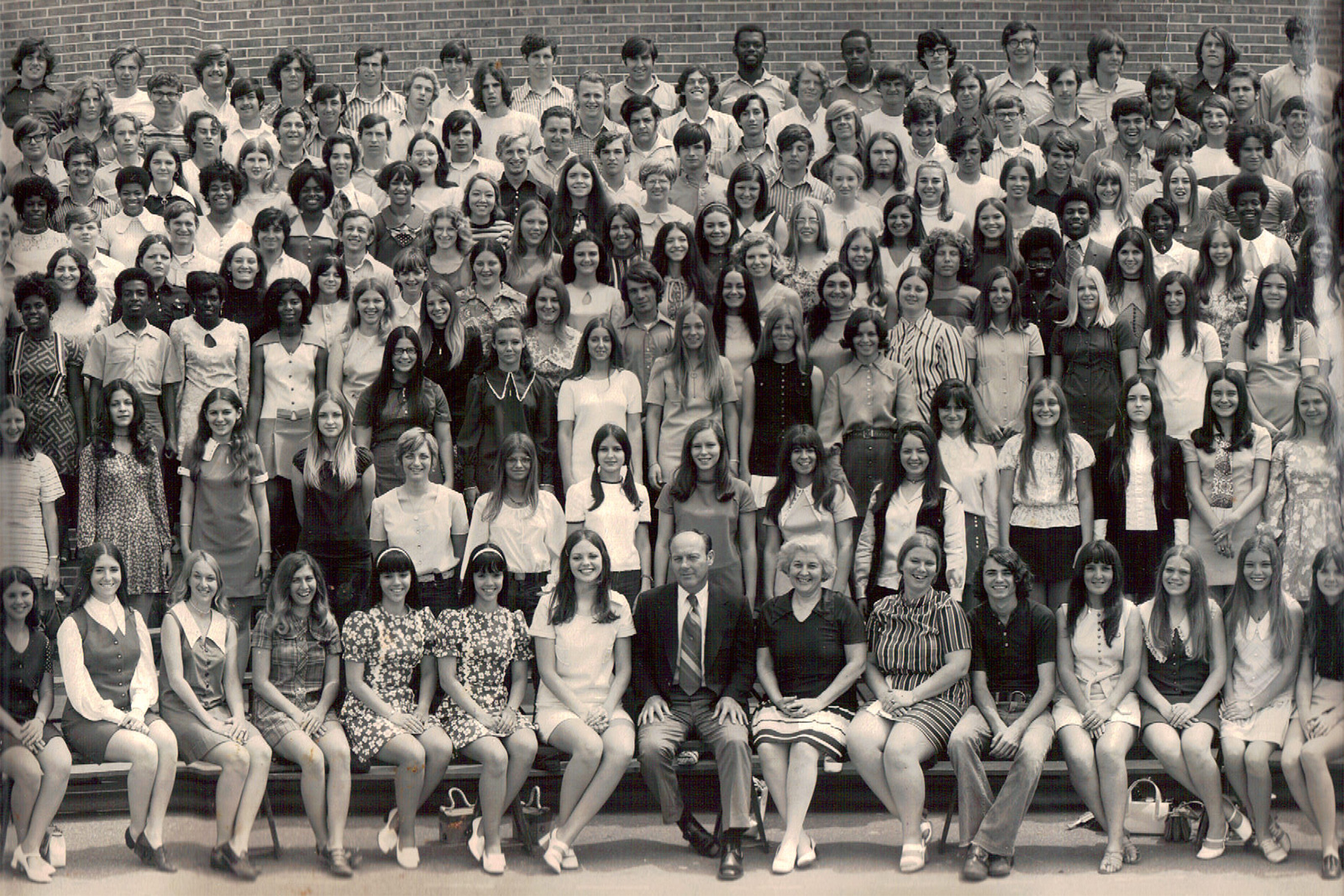

With the economic recovery and appearance of the lBaby Boomer generation, a new social order and hierarchy appeared. Industrial design, and the ideology on which it was based, mass production, experienced its golden years.

The Baby Boomers had clear, simple, and unchangeable rules: Their work place is an office, their responsibilities at work are clear; they know what they need to do and how to do it. There is a set schedule with a specific start and end time to work. The company provides social stability; it makes all the sense in the world to be a businessman and act like one.

Social success is reached through a hierarchical order tied to that of the company. The old workers teach the new; having many years of experience is the path to progress at work and in society. You start as the bellhop and one day you will end up being the director of the hotel. Work guarantees your progress. You can get married, have children, own property. The objects designed during this era have the same hierarchy and order. Products represent your social status, and style is just as important as function. Just think about Car tailfin.

For example, General Motors created a range of automobile brands, each of them targeted a concrete segment of the population. From the young man with little resources to the well-off family, everyone was able to find their brand within the GM world. Starting with Chevrolet, and in ascending order, Oakland, Oldsmobile, Buick, LaSalle, and finally Cadillac, the luxury brand.

They are no longer designing cars, they are designing lifestyles. Designers become stars. The design and designed products represent hierarchy, order, company, business, strategy. The designer holds the place that social context and history have reserved for him or her.

The new revolution, the new order, seek a new designer

The rules have changed: now your work schedule, your workplace, financial success being tied to work, all of this is unclear. Knowledge is not obtained hierarchically, you do not have to spend decades in a company in order to move up within it. All of the rules that the Baby Boomers had written flew out the window some time ago.

The technological developments and the crisis, which is not only Spanish, but global, threatens the vision of design understood as “product as object“. Today we move in a design understood as “product as design“. If in post-war American society consumerism was king and what you possessed was what defined you, in our society what you possess has lost importance, it is what you obtain in exchange, it is the experience that truly matters.

We no longer design for Baby Boomers ready to buy a product that symbolizes a certain social status, now we design for Millenials who do not respect hierarchies. Our users want to listen to music, not buy a CD (Spotify), they want to move around the city, not have a car (Uber), they need a place to spend a few nights, not a hotel (Airbnb).

In today’s economy, and even more likely in the economy that is being born today, everything can be shared, rented, borrowed, or exchanged for a fraction of what it would cost to obtain a product or service through a traditional channel. The new labor relationships are enemies of the old hierarchy.

Everything changed when we started relating to the new consumers. What does this mean for us, the designers? How does the new type of relationship between users and products affect us? The era of products as differentiators, as defining a social status, is reaching its end. The richest person in the world will surely have an iPhone, just like many of you that are reading this post.

The new generations prefer to work and connect in networks, to form part of a community. Brands that differentiate can no longer isolate, design is no longer the tool to stand out; design is used to unite a group, to offer it a shared experience with others. This is our new society, these are our new consumers. I am convinced that this new order needs new ways to design, new processes, and, above all, designers that live and understand the context of the society in which they live.

Follow @NoamMorrissey Tweet