Morality 1

It´s not about how it looks, but how it works

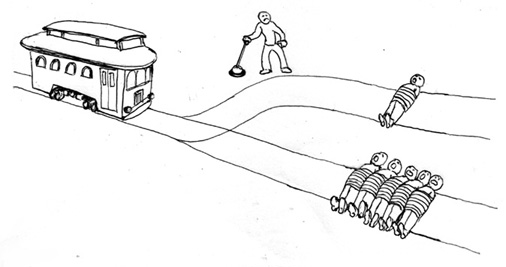

Five people are tied up and lying in the middle of a train track. A train is approaching at full speed. These people are going to irremediably meet their death. You are right next to a lever that when activated would divert the train towards a different track and save the five men.

There’s just one “but”: there is also a person tied to this new track If you move the lever, five people will be saved but one will die. Would you use the lever?

Source: Image in Myanimelist.net – Forum: The trolley problem: a thought experiment

Nine out of 10 people would activate the lever. That seems natural. Morally, it seems an appropriate action to save five lives versus one. Who wouldn’t do that?

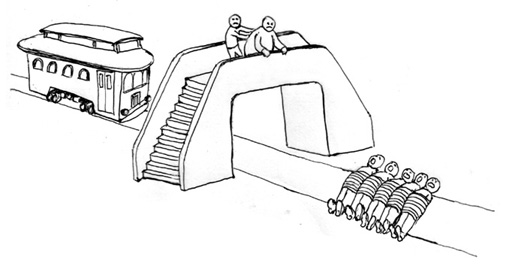

Now, I will put a similar problem forward to you. In this account, like in the previous one, there are five people tied to the train tracks and a train is speeding towards them. This time, you are on an overpass between the train and the five men. The only way to stop the train would be to throw a heavy weight onto the tracks. There is a large man next to you. If you push him, he will fall onto the tracks and you’ll save five lives. In this case, like in the previous one, you have to decide whether to save five lives or to save one. Would you do it now? Would you push one man onto the tracks to save five?

Source: Image in Myanimelist.net – Forum: The trolley problem: a though experiment

The results of this problem are the opposite of the previous one. Nine out of 10 people would not push a man to save the lives of the other five. The responses to these two moral problems seem universal and consistent in their results. The level of education, the sex or the culture people belong to do not matter—the moral responses to these problems are always the same.

This exercise is known as the “Trolley problem“, It has loads of variations, but in its most general formulation, person A can take an action that will benefit a group of people, but in doing so, person B will be unfairly harmed. Under what conditions would it be morally acceptable for person A to violate the rights of person B to benefit the group? Here, you can also listen to the relationship between the “Trolley Problem,” our brains and chimpanzees.

Moral Design

What is the reason why a murder (that is what it is) is justifiable if we do it using an object (a lever), but it seems totally immoral to us when it is we who have to directly take the action (pushing a person).

One interpretation to explain this behavior is the psychological distance between an act and its meaning. The use of a tool (a lever) that functions as an intermediary between an act and its consequences can change our moral perception of that same act.

Design and its moral influence on products and users is not frequently dealt with in our day-to-day lives. That is why I’d like to propose a reflection based on, inspired by and copied from the FARSIGHTED article by Dmitry Fadeyev “Moral Design.” In order to come to talk about morality in design, first we will have to make a small ellipsis.

Most people make the mistake of thinking design is what it looks like. People think it’s this veneer – that the designers are handed this box and told, ‘Make it look good!’ That’s not what we think design is. It’s not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.

Steve Jobs

Design is, then, the projection of how a product should work. On the other hand, the appearance of the products must be a reflection of their functionality; that is they must be honest.

Good design is honest — It does not make a product more innovative, powerful or valuable than it really is. It does not attempt to manipulate the consumer with promises that cannot be kept.

Dieter Rams

From the design world, we generate product usage patterns (designs) that affect our lives. If these patterns serve to improve, elevate and enrich our lives, it could be said that a usage pattern (design) ) is moral. Now, as in the case of the “troley experiment” defining a design pattern as moral or immoral lies in a small but decisive variation. Design patterns that detract from our lives are immoral, and we should start to raise our voices against them.

I share the concern expressed by Massimo Banzi in the video “Connecting“; Too many technological products nowadays require constant attention and unjustified interest.. Unwanted content, overwhelming notifications and, more recently, gamification in certain applications, which do not attempt to transform a task, through games, into one that is more bearable for users, but rather push overconsumption as the sole line of reasoning for an application’s existence. These behaviors in our products are not moral, They don’t respect the intangible asset of time in our user’s life. The aim of most of these products is the product in and of itself. They don’t aspire to improve the lives of their users in any sphere or context.

Once again, the problem of distance

Dan Airely, in a study with 10,000 golfers (you’ll have to search around a bit to find the reference ![]() ) posed a question about how they would deceive the rest of the golfers by moving the golf ball a short distance. The options he proposed to them were: Option A, nudging the golf ball with their golf club; Option B, kicking it; Option C, picking it up with their hands and moving it. Most players preferred option A. This was twice as popular as the other possibilities as a cheating preference. The psychological distance that a golf club gives us is enough so that we have twice as many chances of behaving in a way that is not moral.

) posed a question about how they would deceive the rest of the golfers by moving the golf ball a short distance. The options he proposed to them were: Option A, nudging the golf ball with their golf club; Option B, kicking it; Option C, picking it up with their hands and moving it. Most players preferred option A. This was twice as popular as the other possibilities as a cheating preference. The psychological distance that a golf club gives us is enough so that we have twice as many chances of behaving in a way that is not moral.

Embellishments, complexity added to a product, extraneous elements, etcetera, distance us enough psychologically that we are not able to correctly judge morality or a lack of it in our work. Reducing all this noise and focusing on an object’s or service’s core helps us to not stray from the right path.

Good design is as little design as possible — Less is more – because it concentrates on the essential aspects and the products are not burdened with non-essentials. Back to purity, back to simplicity.

Dieter Rams

In closing, one of those sentences that put to rest any doubts:

All good design is moral design, and only moral design can ever be good.

Dmitry Fadeyev

Follow @NoamMorrissey Tweet